« Hoi An Hoard -- an amazing tale of a buck well spent | Main | New (and lighter) gear for Christmas »

October 23, 2010

Las Islas Coronado, and back to the Yukon

To be honest, after a week of facing muddy, choppy waters in the usually crystal-clear Caribbean, I wasn't exactly looking forward to the three days' worth of diving the usually cold and murky waters of the Pacific off Southern California I had signed up for months ago. I had done enough anchor line diving to last me a while, and by that I mean conditions that require following down the anchor line so that you don't end up somewhere in No Man’s Land.

However, in a prime example of equalizing justice, everything turned out great. The weather -- which is usually iffy in San Diego, with fog and clouds every morning that don't burn off till almost noon -- cooperated with sparkling sunshine, temperatures that were just right, and water flat enough to get places without being rocked around.

For this trip we drove down from Sacramento to San Diego. I was reminded how different driving is from making it through airports and having to pack for flights. Whatever you think you might need is stowed in the vehicle and brought along. Makes no difference what and how much. When you drive you don't pay extra fees and charges and no one X-rays and snoops through your bags. No lecturing that a little pair of cuticle scissors is a deadly weapon and must be confiscated for your own protection. And the trip itself is always an adventure, what with all the cool truck stops, sights, and opportunity to just sit and talk for hours while driving.

This time we passed on paying premium dollars for not-so-premium accommodations and service as we had on our last trip to Wreck Alley. Instead, we set up camp at a lowly Heritage Inn, saving a bundle. It was still just a few minutes away from Waterhorse Charter.

I really didn't know what to expect from the Coronado Islands that were on the agenda for Day One. We got to the marina bright and early at 7:30AM, signed in and completed all the paperwork and wavers, then set up our gear on the boat.

I really didn't know what to expect from the Coronado Islands that were on the agenda for Day One. We got to the marina bright and early at 7:30AM, signed in and completed all the paperwork and wavers, then set up our gear on the boat.

The Humboldt is a marvelous vessel and just about perfect for diving. It can handle some 18 to 20 divers and so the 12 of us from Fisheye Scuba had ample room. There is a cabin with seating on each aide and a kitchen bar in the center. It's small but perfectly adequate and cozy. The dive platform is as good as it gets; you simply step into the water, no big drop here, and no hassle to get to and from the dive platform, or onto the boat for that matter. The Humboldt also has its own compressor, so no need to carry tanks on and off the boat. There's a small upper deck where the captain has his wheel and instruments plus room for a couple of passengers.

On a speedy boat, the Coronado Islands are just over an hour south of San Diego's Mission Bay. They are in Mexican waters, and you're advised to bring along identification, though a passport is not needed. After making sure everyone was on board and ready, we motored off at 8AM, into bright sunshine and a gorgeous morning. The trip was nice and calm, and I spent much of the time examining the coast line in the distance, wondering if it was already Mexico or still Southern California.

With the mainland still faintly in sight, the Islas Coronado came into view. There are four of them and they are small, ranging in size from just a few acres (the Pilon de Azucar, or Sugar Cone), to about three quarters of a square mile (South Coronado). What the Islas Coronado lack in size, they make up in dramatic appearance. They are tall (soaring up to over 700 feet) and rocky, and actually reminded me of what we saw at Saba with its rocks and spires and volcanic look. No one lives here but birds. There are some ranger and research stations, but nothing year-round. The Coronados are very picturesque with a stark beauty.

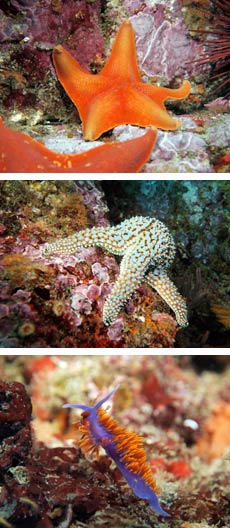

Our first dive site was between two of the islands in a fairly shallow area of about 70 feet. The water didn't look too clear, and it wasn't. For protection I was wearing both my 7-mil wetsuit and a 5-mil shorty with hood on top of it. That also meant a full 30 pounds of weight. Even so I still had to pull myself down the anchor line. At the bottom all that neoprene compressed so much that I had to put what felt like a few hundred psi of air into my BC just to stay afloat. I felt clumsy and gulped too much air. The dive site itself was a small ledge/wall and there was quite a variety of starfish. We didn’t see any kelp, which surprised me. So we swam back and forth the little wall in cold water and modest visibility. Since the site was fairly deep I quickly drained my tank and it was time to get back up the anchor line. The group declared it a good dive. I certainly liked the surroundings, but my taste was for something a little clearer and warmer.

Our first dive site was between two of the islands in a fairly shallow area of about 70 feet. The water didn't look too clear, and it wasn't. For protection I was wearing both my 7-mil wetsuit and a 5-mil shorty with hood on top of it. That also meant a full 30 pounds of weight. Even so I still had to pull myself down the anchor line. At the bottom all that neoprene compressed so much that I had to put what felt like a few hundred psi of air into my BC just to stay afloat. I felt clumsy and gulped too much air. The dive site itself was a small ledge/wall and there was quite a variety of starfish. We didn’t see any kelp, which surprised me. So we swam back and forth the little wall in cold water and modest visibility. Since the site was fairly deep I quickly drained my tank and it was time to get back up the anchor line. The group declared it a good dive. I certainly liked the surroundings, but my taste was for something a little clearer and warmer.

The Humboldt then moved closer to one of the small rocky islands to a place called the Keyhole, named after a small swim-through between the rocks. I had actually seen that before the trip on a YouTube video. After a bit of deliberation, the captain decided it wasn't calm enough to do the site and instead we'd go and play with sea lions. That site, called the "Lobster Shack" (a misnomer as there weren't any), was quite shallow and close to a sea lion rookery. We could actually see the bottom there, which meant the water was reasonably clear.

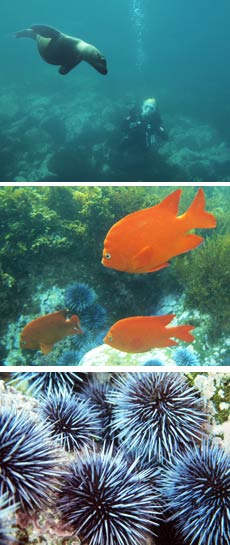

This turned out to be one of the great dives ever. Almost as soon as we got in and descended to the rocky bottom at less than 20 feet, a sea lion appeared and effortlessly darted around us. He left and came back a friend. Now both swam around us and this encounter alone would have made for a great and unforgettable dive. But this was just the start. Soon several more young sea lions appeared, playing with each other, checking us out, and just generally having a grand old time. I was mesmerized by the display that was getting better and wilder as time went on. The sea lions put on a show that I'll never forget, frolicking, darting, playfully pecking at each other, all at fluid, breakneck speed. Occasionally, one would examine us, come closer, then dart away. Some came right at us but then veered off at the last moment to avoid collision. None of that felt threatening, though. They were so much faster and more mobile in the water than us divers that all we could do was watch the spectacle.

This turned out to be one of the great dives ever. Almost as soon as we got in and descended to the rocky bottom at less than 20 feet, a sea lion appeared and effortlessly darted around us. He left and came back a friend. Now both swam around us and this encounter alone would have made for a great and unforgettable dive. But this was just the start. Soon several more young sea lions appeared, playing with each other, checking us out, and just generally having a grand old time. I was mesmerized by the display that was getting better and wilder as time went on. The sea lions put on a show that I'll never forget, frolicking, darting, playfully pecking at each other, all at fluid, breakneck speed. Occasionally, one would examine us, come closer, then dart away. Some came right at us but then veered off at the last moment to avoid collision. None of that felt threatening, though. They were so much faster and more mobile in the water than us divers that all we could do was watch the spectacle.

While the sea lions stole the show, there were a lot of other interesting things to see in the shallow and brightly lit water. An abundance of orange garibaldis were not afraid of divers and came very close. At one time I videoed one as it swam around me a full 540 degrees. And there was the usual assortment of urchins, sea stars and nudibranchs.

Eventually we did get cold and went back up to the boat, laughing, comparing notes and reliving the thril. I'll never forget this dive.

The ride back to San Diego was equally wonderful. Sunshine, calm water, perfect temperature, and the Islas Coronado slowly disappearing in the distance. But there was more. The captain stopped the boat. Whales. We saw the telltale red plumes of krill that whales like so much, and then some large blue whales breaching the surface. We cruised a bit to get a good position to see the whales while keeping a lawful distance, and there they were, scooping up krill, blowing air, and even doing the telltale whale tail flip as they descended. But even that wasn't it. Soon we were followed by dolphins that sprinting and jumping through the wake of the speeding Humboldt. The boat moved fast and we could see the dolphins' athletic bodies working to keep up. Eventually they fell back.

The next day was all wrecks. But what a difference conditions can make. The last time I went down to see the wreck of the Canadian destroyer Yukon, the visibility was poor, the weather dark and gray, and the water miserably cold. This time we again had to descend through 30 or 40 feet of greenish murk, but underneath the water was remarkably clear. The big wreck was far more visible and with that we got a sense of the sheer size of the sunken destroyer rather than just parts appearing out of opaque water. I felt far more relaxed in this kind of visibility, and at 56 degrees Fahrenheit the water mercifully was almost ten degrees warmer (though still cold). This time we could do some actual exploring and seeing the sights. No penetration, though. Not with just a single 80 cubic feet aluminum tank full of air at 90 feet. So I enjoyed the spectacular sight and the growth on the wreck, most noticeably the large white plume metridium anemones and the incredibly colorful strawberry anemones that really look more like coral.

The next day was all wrecks. But what a difference conditions can make. The last time I went down to see the wreck of the Canadian destroyer Yukon, the visibility was poor, the weather dark and gray, and the water miserably cold. This time we again had to descend through 30 or 40 feet of greenish murk, but underneath the water was remarkably clear. The big wreck was far more visible and with that we got a sense of the sheer size of the sunken destroyer rather than just parts appearing out of opaque water. I felt far more relaxed in this kind of visibility, and at 56 degrees Fahrenheit the water mercifully was almost ten degrees warmer (though still cold). This time we could do some actual exploring and seeing the sights. No penetration, though. Not with just a single 80 cubic feet aluminum tank full of air at 90 feet. So I enjoyed the spectacular sight and the growth on the wreck, most noticeably the large white plume metridium anemones and the incredibly colorful strawberry anemones that really look more like coral.

Predictably, my bottom time was cut short not by a lack of air, but by rapidly diminishing nitrogen time. 25 minutes into the dive I was down to three or four minutes and we had to start our ascent back up.

45 minutes later we were in the water again for another dive to the Yukon. By now I felt almost comfortable with the big wreck, but the time for exploring again was short. On this second dive dive to 85 feet, I ran low on nitrogen time after just 20 minutes. I crossed over to the radio tower buoy line, signaled Carol, who was on Nitrox and had much more bottom time, that I had to go up. Then Tom, the owner of the Fisheye Scuba dive shop that had arranged the trip, and I slowly made way back up the line.

Our luck with the weather held up for a third day as we were again greeted by bright sunshine and nearly flat water. Since part of the group was doing a wreck diving class and they weren’t quite done with their training requirements, we went back to the Yukon for one more dive. There is a total of five anchor lines, and this time we descended down to the radio tower that's roughly in the middle in the ship. The visibility wasn't quite as good as the day before, but still in the neighborhood of 40 feet, which meant we could see things. We swam towards the stern of the ship and then over it, and saw the massive propeller assembly that is almost completely covered in white metridians. Interestingly, while every inch of the top of the ship is covered in anemones and other growth, the bottom/outside/hull often still shows the unmarred paint. There is also kelp on the exposed hull. It sways back and forth and helps divers to see current.

As a wreck specially prepared for divers, the Yukon has large rectangular cutouts all over the ship. This makes for easy access for those qualified to enter wrecks. There is, however, fairly strong surge -- strong enough in places to suck you in and spit you back out.

Each dive trip adds to experience, and what I took away from this one are some thoughts about depth and temperature.

When you first start diving, water temperature and what to wear for any given dive is hit and miss, and the difference between a thick wetsuit and a thin one seems academic. You then quickly learn that wearing the right suit is one of the most important decisions to make for a comfortable, enjoyable dive. For example, diving the Yukon with just a 7-mil suit last year was a miserable experience where being cold was all I felt. So cold that I was shivering and had to skip dives, which is never something you want.

This time I wore a 5-mil shorty with integrated hood over the 7-mil wetsuit, and that made a huge difference. My body stayed warm through all the dives in the mid-50s water. The shorty had a zipper from the bottom all the way up to the hood, which meant it was also quick and easy to put on.

On the flip side, this added another thick layer of compressible neoprene, and that greatly affects buoyancy. While on top, you are buoyant enough to need a large amount of weight. Even with a full 30 pounds, which is as much as my Scubapro NightHawk BC can accommodate, I still had to pull myself down the anchor line. At depth, all that neoprene compressed so much that I became very negatively buoyant and had to add a lot of air into the BC, and even relatively small changes in depth affected buoyancy. You can, of course, go with less weight and simply pull yourself down the anchor line, but then there's the risk that you may not find the line to go up and have to ascend without line, and then you do not want to be so light that you lose control of the ascent speed.

I also learned that a good seal on your gloves makes a big difference. While wetsuits provide protection by allowing in a small water layer that warms up, gloves that do not seal well allow in too much water and your hands quickly get cold. This time I wore a new set of gloves that were thin enough to allow me to operate the cameras, but had excellent sealing via a velcro wrist band. This worked great. While the 3-mil neoprene was on the low end of protection against the cold, the seal was so good that my hands stayed just warm enough.

Another observation was the great impact of dive profiles on air consumption and allowable bottom time. When I look at most of my dives once they are uploaded to the SmartTrac software on my PC, I see a descent to the maximum depth of the dive within the first few minutes, staying at that depth for just a minute or so, then usually a linear and gradual ascent. That's because in most dive sites that include slopes or reefs, you drop to the lowest point, then work your way up the wall or slope and then play around on top of the reef or wall until it's time to go up. You could call this a "stairs" profile where you take the elevator to the bottom, then walk back up the stairs.

With "stair" profiles you can go to 120 feet and still have a dive lasting more than an hour on a standard 80 cubic foot tank. That's because the average depth of the dive will be just 30 to 50 feet, depending on the depth of the top of the reef where you spend most of your time.

With deep wrecks (or deep reefs or any dive where you have to first drop a long distance), you dive a "square" profile, which means you drop down to your maximum depth, stay there for the duration of the dive, then come back up the line. This way you spend much more time at depth, drain your tank much faster because you breathe air that is more compressed, and accumulate nitrogen more quickly, reducing your bottom time.

In each of my dives to the Yukon the factors that determined the length of my dive were first, my remaining nitrogen time; second, temperature; and only third remaining air in my tank. All my dives were between 30 and 40 minutes. On each I used up all my allowable nitrogen time even though I never went deeper than 85 feet, and on each I returned with plenty enough air left in my tank.

I also noted that just as nitrogen accumulates in your body, exposure to the cold also seems to accumulate. I didn't feel cold on three wreck dives the second day, but on the third I was already shivering after the first dive. And so I skipped the final dive which was to the wreckage of the NOSC tower, a structure built in 1959 and used through the 1980s until it was toppled during an El Nino storm. Today it is a twisted mass of girders sitting in about 60 feet of water and reaching up as high as 30 feet. Carol reported it a fascinating dive site with wondrous colors and teeming life, including an abundance of some of the largest starfish seen anywhere.

I should add that Waterhorse Charter experienced tragedy when a diver died on the Yukon in September of 2010. It was a 39-year-old with plenty of experience who did the dive by himself. He was last seen apparently photographing something in the sand on the bottom by the Yukon. Upon return to the boat, it was noticed he was missing but by that time it was already too late. This tragic event will undoubtedly hang over the operation as a reminder that accidents can and will happen, and that diving is serious business that as adults we engage in knowing the risks. Quite obviously, dive operators must observe and practice the highest standards, but beyond that it would be most unfortunate if lawyers and grieving parties sued and regulated diving out of business. As is, dive operators offer fewer and fewer services in order to protect themselves from being held liable, essentially reducing themselves to being "taxi services." Insurance companies, which once drove muscle cars out of business and are now making healthcare increasingly unaffordable with ever-rising rates, may also end up making dive operations economically unfeasible. So let's hope reason will prevail.

Posted by conradb212 at October 23, 2010 8:38 PM