« An Exciting Trip "Home" | Main

August 02, 2016

Diving the North Carolina coast

The waters off the coast of North Carolina are known as the Graveyard of the Atlantic. That's because when the warm Gulf Stream meets the cold Labrador currents, things can get quite rough. That primarily goes for North Carolina's Outer Banks, that thin strip of sandy dunes that can be as far as 30 miles away from the mainland. South of that, starting at Cape Lookout, is a less rugged and mostly south-facing 85-mile stretch known as the Crystal Coast where, according to tourist brochures, the waters can be as warm and clear as in the Caribbean.

Having fond memories of summer vacations spent on the Outer Banks decades ago, we made the 530 mile trek from East Tennessee to Morehead City for a couple of days of diving with the folks of the Olympus Dive Center, which is located on the peninsula facing Bogue Sound. The company began as a boat charter business over 40 years ago, the dive shop itself was built a few years later, and their primary dive boat, the 65-foot Olympus, has been serving divers for 30 years.

Like most well-established dive shops, Olympus is an interesting place. There's an eclectic mix of ScubaPro and other dive gear, useful accessories, spare and repair parts, bags, cameras, lights, clothing and also numerous fascinating mementos from decades of exploration under the seas. The shop's founder, the late Captain George Purifoy, is credited with having discovered and identified several major wrecks, most notably the USS Schurz, a 295 foot World War I cruiser that sank in 1918, and the German submarine U-352 that went down in 1942 after mistakenly taking on a US Coast Guard cutter and getting the short end of the deal.

Needless to say we wanted to dive the U-352 as, given the notoriety of the Nazi wreck, we assume most divers new to the area probably would. We put our gear on the spacious dive deck of the Olympus, set up what could be done ahead of time, and then retired to our home for this trip, the Island Inn across the Atlantic Beach Bridge over Bogue Sound. Alarms were set for 5AM as divers were expected at the dock by 6AM sharp.

We had brought our own tanks rather than renting them at the dive shop, and they were still filled with 33% Nitrox from a prior trip, too "hot" for the 120 to 130 feet of the deeper wrecks we planned to dive. We had that toned down to 30%, good for a maximum depth of 124 feet when observing a PPO (partial pressure oxygen) of 1.4 atmospheres.

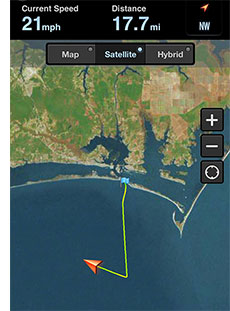

The Olympus left port around 7:30AM, after every diver had collected a numbered "boarding pass" and given it to 1st Mate Bud Daniels so he could do his roll calls after every dive — a clever solution of keeping track of divers and making sure they're all present and accounted for after a dive.

This is when we began learning the realities of North Carolina diving. Unlike in most parts of the world where there's a set schedule of dive sites every day, or where divers can request a site, off the coast of North Carolina it all depends on the conditions. No matter what the weather forecast says or what the skies look like, the situation out on the open sea may be different, and it can change at the drop of a hat. So the Captain, in constant communication with other boats and various services, decides when and where to go.

How can it be so difficult to figure out what conditions to expect? That's because the Eastern continental shelf is relatively shallow and one has to travel pretty far out on the open sea to reach depths of 120 to 130 feet where most of the interesting historic wrecks lie. That means 30 to 40 mile boat trips right to the border of the gulf stream where currents and ever-changing temperatures mean anything can happen.

For us, the initial word was that it was 50/50 on whether we could make it to the deep sites. Once past Beaufort Inlet, where the incoming swells mean it's always rocky, the seas were not too bad and after half an hour or so the Captain announced we'd be headed for the wreck of the Aeolus, a 410-foot tanker sunk in 1988 as part of the state's artificial reef program. The Aeolus now rests in about 110 feet of water, maybe 30 miles out. That was good news to us because the U-352 sits in the same direction, just another five miles farther out to sea. So we hoped to see the submarine on the second dive.

For us, the initial word was that it was 50/50 on whether we could make it to the deep sites. Once past Beaufort Inlet, where the incoming swells mean it's always rocky, the seas were not too bad and after half an hour or so the Captain announced we'd be headed for the wreck of the Aeolus, a 410-foot tanker sunk in 1988 as part of the state's artificial reef program. The Aeolus now rests in about 110 feet of water, maybe 30 miles out. That was good news to us because the U-352 sits in the same direction, just another five miles farther out to sea. So we hoped to see the submarine on the second dive.

It was not to be. A bit later, with the seas getting rougher, the Olympus made a hard turn to the right and word came from the bridge that the deep dive program had to be aborted due to unsafe conditions. Instead, we were now heading for shallower waters closer to shore.

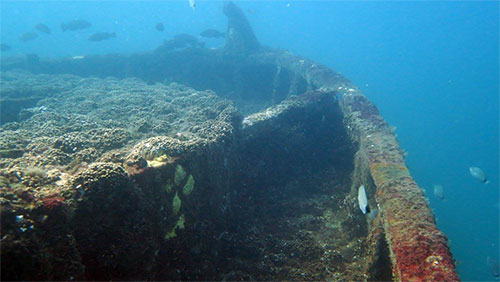

We ended up diving the "inshore" wreck of the 330-foot freighter Indra, also sunk under the artificial reef program in 1992. Depth here was 65 feet, which made for a short descent and much longer dive time. Visibility at the wreck was maybe 45 feet, not tremendous and definitely not the 80-100 feet listed for the month of July and 100+ feet for August.

It was a pleasant dive in 81 degree water and also my first opportunity to experience the "Carolina Rig," which consists of weighted hanglines dropped off the middle and rear of the boat with a horizontal line at 15 feet between them, and a rope down to the anchor line in the front. That makes it easy to find the line down to the wreck, and also helps the 15-foot safety stop at the end of the dive and then heading to the back of the boat and to the ladder.

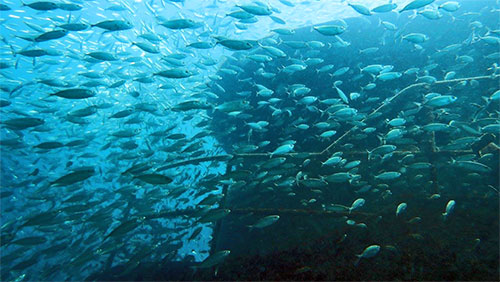

The second dive was to two tug boats — the James J. Francesconi and the smaller Tramp — that had recently (May 2016) been sunk near the Indra. Visibility was less, but still good enough to enjoy the dive and going to both tugs. What made this dive special were massive schools of small fish literally enveloping the wreck in ever-changing speed and formations. What made them stop and start was never obvious as they didn't seem to be afraid of divers. It was totally fascinating to watch them.

The weather forecast didn't look bad for the next day and so we had high hopes to make it to the U-352 after all. Our hearts sank when we saw divers who had arrived at the dock before us take a wait-and-see approach rather than preparing their gear on the boat. And sure enough, the Captain called us together and announced that conditions were rough again, and the most we could hope for was a trip to the shallower inshore sites.

After some more deliberations, the Olympus did indeed take off. The swells at the inlet were quite large and rocked the sizable boat. Once out on the open ocean it calmed down some, but we still saw whitecaps and hit the occasional large swell. The presence of whitecaps is usually our own indicator that it's too rough to dive. Not so much underwater, but getting back on the boat with the ladder slamming up and down. Half an hour into the trip the Captain called it off. Too dangerous. And that was that for us. On the way back through Beaufort Inlet, we saw a large sport fishing yacht almost flop over backward, so big were the swells.

Our experience pretty much summarized the predicament of North Carolina diving. Trips to the deeper wrecks are long, which makes them quite expensive. The water is warmer farther out and the visibility likely better, but you truly never know if you can actually make it out there. On a good day it may be two great days of diving to where you wanted to go. On bad days you don't get to leave the dock at all. In between it's a maybe, and you don't know what to expect.

Our experience pretty much summarized the predicament of North Carolina diving. Trips to the deeper wrecks are long, which makes them quite expensive. The water is warmer farther out and the visibility likely better, but you truly never know if you can actually make it out there. On a good day it may be two great days of diving to where you wanted to go. On bad days you don't get to leave the dock at all. In between it's a maybe, and you don't know what to expect.

That makes planning dives difficult. Nitrox fills cost twice as much as air, and it's really wasted on shallow sites. Planning what gear to take with is difficult as well. We're usually testing cameras on every dive, and depth determines filters, lights and the type of camera we want to take with. Hotel accommodations are expensive, and staying without being able to dive quickly drives up the cost per dive.

While cancelled or aborted trips are frustrating for divers, it's much worse for charter operators who have to deal with disappointed customers. And they never know whether a fully booked boat will result in actual pay or not. The double whammy of environmental conditions and — in the absence of reefs or walls or many other interesting sites — being limited to the relatively small number of suitable ship wrecks makes diving the coastal waters of North Carolina an uncertain proposition.

I certainly don't regret the trip. I love long drives, we had great company in our friends Tom and Donna, the boat rides themselves were wonderful even without diving, the Olympus dive operation was great, and we got to experience not only the ever-changing and often dramatic North Carolina coastal weather and skies, but also managed some beach combing and sight-seeing. Fort Macon alone is worth a trip.

Posted by conradb212 at August 2, 2016 04:55 PM